As animals age, they generally look less good and their telomeres, small structures that protect chromosomes from becoming frayed or tangled, become shorter. In our article we investigated if the effects of age at conception of mothers to the telomeres of their offspring would persist over a subsequent generation (grandoffspring generation), having previously found out that they persisted into the offspring generation.

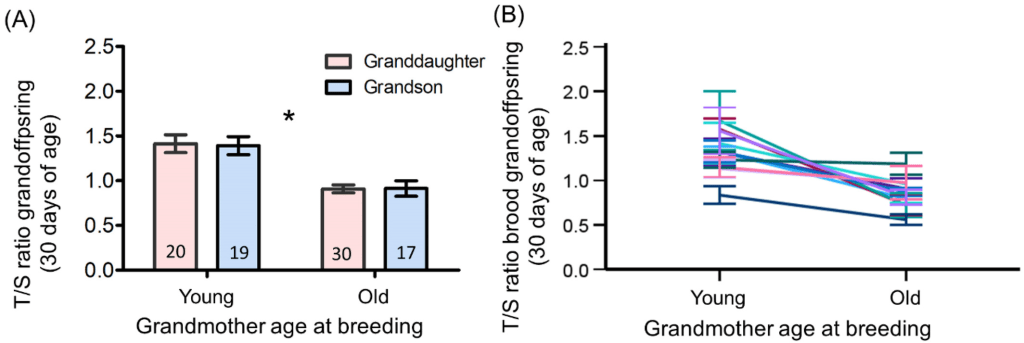

In this new study, we showed that the shortened telomeres found in the joungsters of older grandmothers are also present in their children, i.e. the grandchildren generation – even if the breeding mothers of the 2nd generation were young. This effect was considerable: telomeres were 43% shorter in the offspring of grandmothers who were old at rearing than in the offspring of the same grandmothers who were young at rearing. Shorter telomeres at the time of fledging are associated with a shorter lifespan in zebra finches. These results indicate that it is necessary to look beyond a single generation to explain inter-individual differences in ageing and different age-specific reproductive efforts. The mothers were young at the time of breeding, so effects due to the age of these mothers can be ruled out. It would be very interesting to know whether the effects of the grandmother’s age increase if the mother’s age is also high.

Our data reveal a hidden legacy that can be passed on across generations and has a negative impact on the lifespan and reproductive value of offspring. We stress, therefore, that evolutionary biologists and ecophysiologists need to look beyond a single generation and current environmental conditions to fully understand the causes of inter-individual differences in ageing rates and age-specific reproductive effort.

The article by Valeria Marasco, Winnie Boner, Kate Griffiths, Shirley Raveh and Pat Monaghan is accessible Open Access 🙂

We are very much grateful to the PR team at Vetmeduni for helping us to communicate our work to broader audiences and contribute to our #OutreachMission #OpenScience Vetmeduni PR article (in German and in English).